[ad_1]

Once you get past the better-known gods and monsters of the Greeks/Romans, the Vikings, and the Celts, there’s a ton of cultures in Europe that have mythologies that look pretty damn weird to our modern western eyes. I think few are as weird as that of the Basques.

Why? Well, the Basques are a people who live in the border region of Spain and France, and they have a very insular kind of culture. But not only that: they are different from everyone in Europe. They’re not Latins, Germans, Celts or Slavs. Their language is not related to any European language. In fact, they appear to be the oldest surviving culture in Europe, the last remnants of possibly the earliest (human) people to have moved into Europe. They have lived in the Basque region for at least 7000 but maybe as long as 30000 years.

So they’re a really really old culture, and a really weird culture because of how old they are and how relatively isolated they were for a very long time. And it’s OK for me to call them weird, because I’m a proudly-weird quarter Basque myself. These days, Basques take a lot of pride in their differentness.

The Basques’ religion and myths and monsters are really old too. They’re what academics call “Chthonic”; a mythology that is older than civilization and based on the nature-worship of pre-civilized peoples. And man, are they weird. Let’s take a look just a few:

1. Mari

Mari appears to have been the main goddess of the Basques, and probably the best evidence for those academics who believe in primitive goddess-worship. You know all those weird statues of female “goddess” figures that have been found at ancient sites? Those might just BE Mari.

But Mari isn’t the loving-earth-mother type of Goddess that new-agers and hippies generally envision today. Her traditional appearance was as a woman wreathed in fire; but she could also shape-shift into a goat, tree, or other creatures. She lived in two caves, one during the wet season, the other in the dry season; and her moving from one to the other was what changed the seasons.

According to legend, she would eat stories and lies told by people, and Basque witches would perform magical ceremonies where they would “feed” her lies in exchange for rain. But she also had a taste for cows, which she would be said to frequently steal. On the other hand, if a Basque was lost, legend holds he could shout Mari’s name three times and she would lead him back home. She was a wild nature-goddess who was dangerous to be around but if venerated properly could bring the people the things vital for survival.

When Christianity came to the Basque country, the Basques gradually shifted their devotion for Mari to the virgin Mary, treating the two as the same being, though of course this also whitewashed some of Mari’s darker aspects.

2. Sugaar

Sugaar was Mari’s mate, but way less important, from what we’ve seen, than Mari. His job was mostly to have sex with Mari, which he supposedly did every Friday. Oh, and he looked like a giant fiery snake. Whenever they met, their intercourse created storms. Like Mari, he lived in caves (not the same caves, though). Stories say that he would sometimes be seen flying through the sky (hard not to spot since he was on fire), just before a thunderstorm strikes. Some stories also claim that Sugaar would also punish naughty children who disobeyed their parents; but that’s probably just something someone’s mom thought up.

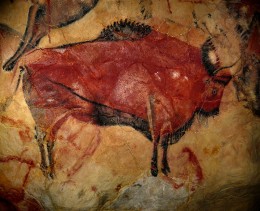

Like the ‘goddess’ image, serpents are one of the oldest figures in human mythological symbolism. Note how the two main gods of the Basques lived in caves; this might be because they date so far back as to be from the time that ancient humans did most of their religious stuff in caves, like the paleolithic caves we see all over Europe.

3. Aatxe

If the first two examples don’t convince you we’re dealing with a stone-age mythology here, Aatxe should. He’s the son of the Goddess Mari. And he looks like a big red bull (though in some legends he could also take the form of a strong young man). Exactly like the kind of bulls we see drawn in ancient cave paintings, including ones in the Basque regions. These cave drawings date back at least 14000 years, and maybe as far back as 36000 years.

Bulls were clearly sacred to paleolithic people, they were an essential part of survival. They symbolized both power and the closest equivalent to ‘wealth’ you could conceive of at the time. They were hyper-masculine, and potentially dangerous.

Aatxe’s job was to hunt down and punish people who had in some way defied or insulted Mari. Of course, he lived in a cave. Legend says he’d come out of the cave at night, especially during storms. When he went out, he’d hunt down wrongdoers, but was also said to protect innocents from danger; like some kind of stone-age Batman (or, I guess, Bullman).

4. Herensuge

Herensuge is the Basque version of a dragon. Only he’s extra-freaky just like all the other Basque monsters: he has seven heads (reminiscent of the later Greek hydra), and he’s super violent. Of course, he lives in a cave. He comes out of his cave only to devour the flesh of animals or humans.

Unfortunately, there’s little surviving pre-Christian lore about Herensuge. There’s plenty of stories from after the Christian era which put him in the pretty typical European role of ‘evil dragon’; with all the stuff you’d expect, like his stealing away princesses to eat later or fighting valiant knights. In one amusing Basque twist to one of these stories, a princess is kidnapped by Herensuge and no one dares to fight the seven-headed dragon until a Basque shepherd and his dog come along. The shepherd frees the princess while his dog heroically fights off the mighty dragon, biting out each of its seven tongues.

Man, even Basque dogs are weird.

5. Akerbeltz

Akerbeltz literally means “The Black Goat”, and he was originally a Basque spirit who protected animals, and took the form of a black billy goat. He was a child or a messenger of the goddess, Mari, and acted as her representative with the “sorginak”, the shaman/witches who were the priestesses of that goddess in ancient times.

The thing is, Akerbeltz looks an awful lot like the very archetype of what would later become the European Christian imagery associated with the devil. So much so that in the medieval period, to the surrounding cultures and the Church, it was seen as proof of the wickedness of the old Basque beliefs. And yet, even after they were all Christian converts, the Basques themselves continued to consider owning a black billy goat as bringing good luck to the farm, and that doing harm to a black billy goat would lead you to be cursed with bad luck.

6. Basajaun

Basajaun are big hairy men of the forest. They are thought of as the ‘old people’ who were in the Basque lands since even before the Basques, according to legend. They are generally shy but friendly to humans (so in some areas these big hairy men are called “Jentil”, a borrowed word derived from Latin for ‘gentle’). They are said to protect animals, knowing all the secrets of animals and plants, and in some cases have thrown rocks at invaders to Basque lands. They’re even credited with having been decisive in helping to defeat the army of Charlemagne when they were invading, causing the death of the famous knight Roland. They allegedly also throw rocks at churches, because they are from the old religion. Of course, they live in caves.

Now, lots of cultures have the story of ‘old people’ who are very like humans but not quite humans, who live in woods or mountains or caves. They may be a kind of species-memory of when there were other hominids, like the Neanderthals. But with the Basques, there’s one difference: the Neanderthals went extinct, maybe as late as 26000 years ago; and the last place on Earth where they lived was in Spain. Remember how I said Basques may have been living in Spain as far back as 30000 years ago?

That means the Basajaun/Jentil stories might not just be some generic species memory. There’s a tiny little chance that it might just be based on actual times Basques and Neanderthals hung out, which to me at least is just a delightfully mind-blowing thought.

7. Gaueko

Gaueko was the evil spirit of the darkness and the night. According to legend he was incredibly dangerous, and would hunt down and kill people who dared to go out in the dark of the night, especially people who publicly boasted about not being scared of the dark. The stories go that you’d first sense his presence by a gust of wind and soft noise. Then you’d hear him whispering “the day is for those of day, but the night is for the night-creature”. And then, unless you were very fast or very lucky, you would see him, in his terrible form, usually as a shadowy humanoid figure but in some stories as a black wolf or hound, and he’d hunt you down.

8. Lamiak

The name Lamiak may be borrowed from the Greek “Lamia”, which in Greek Mythology was a female demon who ate babies and sometimes had snake-like qualities. But in Basque country, the Lamiak were creatures who looked like incredibly beautiful women, who would often be encountered in lonely places near water, brushing their long lovely hair with a golden comb. The only way you could tell they weren’t human was by noticing that they had duck-feet.

Unlike the Greek version of the story, Lamiak were not usually very evil, at least not in the modern sense, but they would often try to seduce men into the sin of lust by becoming their lovers. It was said that hearing the sound of a church-bell would kill Lamiak, which conveniently explains why they’re very rare nowadays.

There was also a male version of the Lamiak, most commonly called a Mairu, who were a bit more creepy. In some stories, they’d go into houses at night and try to have their way with human womenfolk.

9. Anxo

The Anxo, sometimes also called the Tartalo (probably a name borrowed from the Greek for “tartarus”), was the Basque version of a Cyclops. He was a cave-dwelling monster (no surprise there) who lived in the mountains, and liked to cook and eat boys. According to legend, the only way to escape the Anxo is by swimming or tricking him into falling into a well, because the heavy monster would quickly sink into the water and drown.

10. Olentzero

If none of this has yet impressed on your minds just how weird the Basques are, how about the fact that their version of Santa Claus is a crazy monster too? Instead of “Father Christmas” or “St.Nick”, little Basque kids get a visit from Olentzero, who looks like a strong, tall old man (traditionally beardless) in Basque peasant clothes, smoking a pipe with his face covered in soot. In some versions of his legend, he also has glowing red eyes. Nothing ominous about that…

And it gets stranger still: Olentzero isn’t a Christian saint, or indeed a Christian at all. Nor is he a friendly elf. He is, according to legend, the last of the very pagan “hairy men of the woods” I mentioned above. The story goes that one day (on the winter solstice) the ‘men of the woods’ saw a strange star in the sky, and the wisest of their number told them all that it was a sign that Christ was about to be born. So far, pretty typical of a Christmas story. Except then, they all agreed that they didn’t want to live in a Christian world, so they committed mass suicide by throwing themselves off a cliff, all except Olentzero who was left behind.

This story, along with stuff like how they still consider the black goat to be a sign of good luck rather than of evil, reveals a lot about just how tied to a pagan mindset the Basque people remained for a very long time. There were Christian missionaries in the Basque lands since as early as the 3rd century, but by many reports Basque country was mostly still pagan until as late as the 13th Century. They were largely uninterested in becoming Christians for a thousand years. When the Muslims invaded Spain, their 8th and 9th century records list the Basques as being pagan, not Christian; and in Muslim Spain Basques had a reputation for being “wizards”. A Basque cemetery dating to the late 9th century was found without a single Christian (or Muslim) symbol on it. And historical surveys have found that even in the 15th century there were still very few churches in Basque country compared to almost anywhere else in Christian Europe.

Olentzero does give out toys to Basque children just like Santa. But unlike Santa, in Basque folklore he’ll also spend his time hunting down Basque children with a sickle if they stay outside after dark. He’ll also come and cut the throat of any naughty child who doesn’t want to go to bed when their parents tell them to.

With a childhood full of stories like that, no wonder the Basques are weird.

[ad_2]

Source link