[ad_1]

Well here we are, we’ve reached that time of year again at which our yearly ritual of resuscitating small internal combustion engines from their winter-induced morbidity is well under way. It’s lawn mowing season again, and a lot of us are spending our Saturday afternoons going up and down our little patches of grass courtesy of messers Briggs and Stratton. Where this is being written, the trusty Honda mower’s deck has unexpectedly failed, so an agricultural field topper is performing stand-in duty for a while, and leaving us with more of the rough shag pile of a steeplechaser’s course than the smooth velvet of a cricket ground. Tea on the lawn will be a mite springier this year.

When you think about it, there’s something ever so slightly odd about going to such effort over a patch of grass. Why do we do it? Because we like it? Because everyone else has one? Or simply because it’s less effort to fill the space with grass than it is to put something else there? It’s as if our little pockets of grassland have become one of those facets of our consumer culture that we never really think about, we just do.

If you consult the only history books worth reading, you’ll find that in Days Of Old there would have been a grassy area kept free of trees and other growth surrounding castles and other military installations, for defensive purposes. This can clearly be seen in contemporary films. As mediaeval castles slowly evolved over the centuries into aristocratic homes, so did the practice of surrounding them with close-cropped grassland. The mowing would have been performed by animals, but the result would have been to retain something starting to resemble a rough lawn.

When aristocratic homes ceased to have any military purpose, their gardens became an art form in themselves. Formal gardens took the lawn and incorporated it into their designs, maintaining it with legions of gardeners using hand tools. The lawn was thus an extreme status symbol; to have one you had to be in a position to employ people simply for the useless task of maintaining grass for pleasure.

So by the 19th century, combining the insatiable desire of the upwardly mobile Victorian middle class for status symbols with the seemingly limitless ingenuity of the engineers of the Industrial Revolution, it was inevitable that technology would democratise lawn ownership and set our civilisation on the slow but inexorable path to our current Briggs and Stratton servitude.

Lawnmowers

We have an engineer from Gloucestershire, England, [Edwin Budding], to thank for the first lawn mower. His 1830 rotating blade cylinder derived from shears used in the wool industry and driven through a gear train by a roller in contact with the ground as the operator pushed it is a design that has stood the test of time. The gears may have been replaced by a chain, and the whole machine may have been made much lighter, but you can still buy substantially similar mowers today.

[Edwin Budding] is remembered in the 21st century through a charity in his name, the [Budding] Foundation operates a horticultural equipment museum and works in advancing education and opportunities for young people. You might ask yourself what other relevance he has for a Hackaday reader, until you learn that he is also credited with the invention of the adjustable spanner. Most of us will have one of those in our possession even if we have never used a push mower.

The [Budding] mower may have been the first machine to perform the task, but it and its imitators would still have been used by professional gardeners in employment rather than by homeowners in the way we might use our mowers today. Thus, although there were improvements to the design of the push mower through the rest of the century, it was not until the 1890s that inventors addressed themselves to the task of creating a powered mover.

The Lancashire Steam Motor Company, of Leyland, UK, (incidentally the ancestor company of all those dubious-quality British Leyland cars of the 1970s) is credited with the first steam-powered mover, and over the decades before the First World War there appeared a variety of similar designs. They were however heavy, unwieldy, and inconvenient, so it was not surprising that concurrent development led to the first gasoline-powered mowers. The Ransomes machine of 1902 is recognised as the first gas-powered mower to be manufactured, and when compared with the Coldwell steam engine machines, had a clear size advantage.

![An early Atco cylinder motor mower. Mike Peel [CC BY-SA 4.0].](https://hackadaycom.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/powis_castle_2016_072.jpg?w=250&h=167)

In the years following the First World War both the demands of an emerging suburban middle class for labour-saving devices for their lawns, and the refinement of internal combustion engines, led to new machines with much more modest sizes appropriate for domestic use.

The 1921 Atco mower is visibly a [Budding]-style machine with a Villiers motor and chain drive mounted on top of it, and was an instant success. The petrol cylinder mower is now a design that can be seen on sports pitches and golf clubs worldwide, and is still in production from multiple manufacturers.

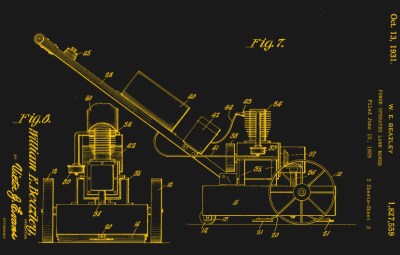

Meanwhile during the same period other inventors were pursuing rotary mover designs. One of the first American models came from [William Beazley], whose 1929 rotary mower starts to look slightly similar to the models we’d be familiar with today. However one aspect of the design reveals its early provenance, instead of mounting the motor on its side as we’d expect, it has an upright motor and a right-angle drive through a bevel gearbox. It was only through the next decade that engine manufacturers started producing motors designed to mount on their sides, and thus the rotary mower’s surge in popularity came at a later date.

Lawnmower Hacking

It’s all very well having a history lesson, fascinating though it is, but this is a hardware hacker’s site. What can you do with a lawn mower? To answer that query it’s worth looking at what parts a mower contains, as well as why an old mower might come into your possession.

The most basic gasoline powered lawnmower will have a rectangular pressed steel cover for the blade, upon which the engine sits with its crankshaft vertical, and which has four wheels, one at each corner. You will usually receive it because, like our Honda, the pressed steel has succumbed to the inevitable rust, and the whole thing is starting to disintegrate. Thus if you can undo a set of bolts seized up by rust and repeated heat cycles, the chances are you can retrieve a perfectly serviceable engine and a set of plastic wheels.

More fancy mowers will be self-powered, and will have a rear axle with some form of gearbox, and either a shaft drive or a belt drive. Domestic ones are a bit of a gimmick, not good for much more than moving the weight of the lawnmower itself, but if you can lay your hands on a professional mover of the type used for playing fields or similar then you have something with a lot more pulling power.

The vertical crankshaft motors are not usually the most high-tech of devices, but what they lose in that direction they make up in simplicity and reliability. The Briggs and Stratton sidevalve for example has been in production in substantially similar form for many decades, and if well-maintained is an engine which will remain a faithful servant. What you use them for is limited only by your imagination, but a quick YouTube search finds vertical crankshaft lawn mower engines in hovercraft, on frightening motorised bicycles, and in generators. Meanwhile we’ve featured one used to power a rudimentary outboard motor.

So as you trudge up and down your little piece of green sward, consider the machine that’s slowly vibrating the feeling from your fingers. You know a little about its history now, what are you going to do with its parts when it shuffles off this mortal coil?

Header image: Colin Thackeray [CC BY-SA 2.0].

[ad_2]

Source link