[ad_1]

Sixty years ago this month, an unassuming but gifted engineer sitting in a lonely lab at Texas Instruments penned a few lines in his notebook about his ideas for building complete circuits on a single slab of semiconductor. He had no way of knowing if his idea would even work; the idea that it would become one of the key technologies of the 20th century that would rapidly change everything about the world would have seemed like a fantasy to him.

We’ve covered the story of how the integrated circuit came to be, and the ensuing patent battle that would eventually award priority to someone else. But we’ve never taken a close look at the quiet man in the quiet lab who actually thought it up: Jack Kilby.

Keeping the Lights On

What becomes of one’s life is often largely determined by circumstances of birth, and Jack Kilby came along at just the right time in just the right place. Born in 1923 in Missouri, Jack St. Clair Kilby was very much a product of his time and of the American midwest. His father was an electrical engineer who relocated the family to Kansas when Jack was a baby to run a small electric power company. Jack came of age watching his father keep the lights on for far-flung customers spread over the western Kansas prairie.

As interesting as Jack found the family business of power distribution, the burgeoning radio industry was also to have a major influence on him. When a blizzard knocked out lines and plunged his father’s customers into darkness in 1937, young Jack watched as his dad enlisted local hams to coordinate repairs. That so much could be accomplished so quickly by the amateur radio operators left an impression on Jack, and electronics became another passion for him.

Determined to follow his passion to the top, Jack took the entrance exam for MIT after high school. He failed to make the cut, however, and so entered the University of Illinois in 1941. The bombing of Pearl Harbor four months later prompted Jack to enlist, and he quickly found himself in the Signal Corps in charge of radio gear. He spent much of the war with the Office of Strategic Services, the forerunner of the CIA, helping to establish resistance networks in the Pacific Theater. His job consisted mainly of keeping the bulky backpack radios issued to commandos running, a challenging job which once saw him returning from Calcutta with a load of black-market parts to build smaller, better radios for the job.

After the war, Kilby returned to school on the G.I. Bill. He got his degree in electrical engineering in 1947, the year that the transistor was invented at Bell Labs, and earned a Master’s at the University of Wisconsin in 1950. His work with a firm making miniature circuits on ceramic substrates led to an interest in semiconductors, and in 1958 when Texas Instruments recruited him on the promise of being able to work on component miniaturization, he made the move to Texas.

The New Guy Makes a Splash

Jack joined TI in June 1958. Unbeknownst to him, the custom was for everyone to take their summer vacation at the same time in July. So mere weeks after starting his new job and with no accrued vacation time yet, Jack found himself alone in quiet labs. He turned the quiet time into productive time.

Radio was a big part of TI’s business in those days, so Jack had been given a broad assignment to look for ways to improve the intermediate frequency amplifier, or I.F. strip. As he pondered the problem, he began to see that a block of semiconductor could be used to hold all the components needed for a circuit, and that the components themselves could be built up from other blocks of semiconductors.

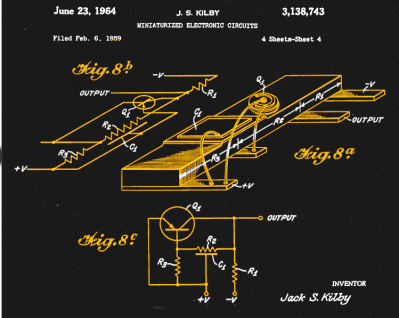

Jack wrote his idea for a “monolithic circuit” down on July 24, 1958. His management gave him the green light to develop it, and by September his team had a working oscillator build from a small slab of germanium. Although the future would belong to silicon ICs, which were almost simultaneously being invented by Robert Noyce at Fairchild, the age of the integrated circuit had been born.

Kilby would go on to enjoy a long and rich career at Texas Instruments, retiring after 25 years. He would accumulate a galaxy of awards and accolades, including induction into the National Inventors Hall of Fame, at least four separate IEEE awards plus having an award named in his honor, the National Medal of Science, the National Medal of Technology, a Kyoto Prize, and in 2000, the Nobel Prize in Physics.

For a fellow who considered himself to be a simple electrical engineer, the attention seemed like just a lot of fuss, right up until his death in 2005. But the critical insight Kilby had in that vacant lab ended up changing the world, and that’s certainly worth a little attention.

[ad_2]

Source link