[ad_1]

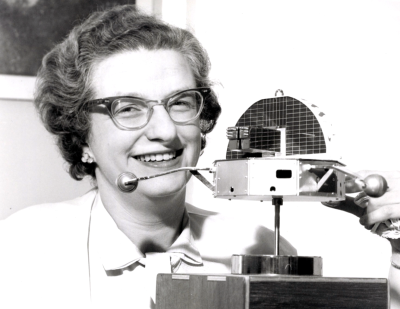

When she was four years old, Nancy Grace Roman loved drawing pictures of the Moon. By the time she was forty, she was in charge of convincing the U.S. government to fund a space telescope that would give us the clearest, sharpest pictures of the Moon that anyone had ever seen. Her interest in astronomy was always academic, and she herself never owned a telescope. But without Nancy, there would be no Hubble.

Goodnight, Moon

Nancy was born May 16, 1925 in Nashville, Tennessee. Her father was a geophysicist, and the family moved around often. Nancy’s parents influenced her scientific curiosities, but they also satisfied them. Her father handled the hard science questions, and Nancy’s mother, who was quite interested in the natural world, would point out birds, plants, and constellations to her.

For two years, the family lived on the outskirts of Reno, Nevada. The wide expanse of desert and low levels of light pollution made stargazing easy, and Nancy was hooked. She formed an astronomy club with some neighborhood girls, and they met once a week in the Romans’ backyard to study constellations. Nancy would later reminisce that her experience in Reno was the single greatest influence on her future career.

By the time Nancy was ready for high school, she was dead-set on becoming an astronomer despite a near-complete lack of support from her teachers. When she asked her guidance counselor for permission to take a second semester of Algebra instead of a fifth semester of Latin, the counselor was appalled. She looked down her nose at Nancy and sneered, “What lady would take mathematics instead of Latin?”

Reaching for the Stars

For college, Nancy chose Swarthmore. They had a strong astronomy program founded by Susan Cunningham, who’d studied under Maria Mitchell at Vassar. Unfortunately, World War II was in full swing, and many of the teachers had left to help with the war effort.

The school’s observatory was in a sad, neglected state and was being used as a silo for onion storage by some locals. Determined to study the cosmos, Nancy and another student took the telescopes apart, cleaned and reassembled them, and made adjustments so they would work better.

Nancy graduated with a BA of Astronomy in 1946 and went to the University of Chicago for her PhD. After graduating, she stayed on to work at the university’s Yerkes Observatory in Wisconsin. One day, as she was trying to determine the relationship between the composition of a star and its location within a galaxy, she observed a star with unusual emission spectra. It seemed a bit strange, but she didn’t think much of it. She wrote a two-page note about it and went back to work. The star she observed, a binary system later named AG Draconis, would turn out to be her lucky star. It only exhibits such bursts of activity for about 100 days every 10 or 15 years.

While Nancy greatly enjoyed teaching and research, she figured that a woman would never get tenure at a research institution. She changed her specialization to stay close to research and took a position in the radio astronomy program of the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) in Washington.

A few years into this post, she received an unexpected invitation to attend the dedication of a new observatory in Armenia. The new observatory’s director had read her two-page note about that unusual star she’d seen at Yerkes and was intrigued by her discovery, so he invited her to take the place of someone who’d had to drop out.

Nancy only had about four weeks to get permission from the Navy and secure entry into the Soviet Union during the Cold War, but she managed. The news of her invitation traveled quickly around the NRL, and they asked her to speak about her trip and lecture her colleagues when she returned.

NASA Brass

Nancy enjoyed lecturing about astronomy to an audience already versed in engineering and physics because she could explore the topics more deeply. She gained a lot of recognition and notoriety from giving these lectures, and when NASA was formed in 1958, the powers that be came to her to recommend someone who could start a space astronomy program. Nancy took this as a suggestion that she submit her own name. It was difficult to leave research, but she couldn’t resist the opportunity to influence the future of astronomy for decades to come.

Nancy was the first female executive employed by NASA. She was responsible for developing several space astronomy programs, budgeting them, and seeing them through to completion. She oversaw the development of astronomical satellites and was involved in launching three Orbiting Solar Observatories that used gamma and x-rays to study the Sun from low-Earth orbit.

One of her duties was taking the temperature of the astronomy community. She traveled all over the U.S. with NASA engineers in tow to find out what astronomers wanted most from the newly formed organization. The engineers were there to verify the feasibility of their wishes. Most of them said they wanted a telescope in space, but they didn’t all agree. Many respected astronomers were anti-space, and believed that everything could be done better from the ground as long as they kept building bigger and better telescopes. Before Nancy convinced Congress, she had to convince the astronomy community.

Mother of the Hubble

Nancy has often compared Earth’s atmosphere to an old stained glass window. We can see through it, but dust particles and irregularities in the glass distort the view and obscure a lot of detail. Earth’s atmosphere acts the same way; it blocks some light completely, and distorts the light that does get through.

Much of the light that gets blocked is crucial to furthering our understanding of the universe because it allows us to measure the speeds of stars and galaxies. Putting a telescope above the atmosphere seemed to be the leap that science needed.

The idea of putting a telescope in space was not a new one. A Princeton professor, Lyman Spitzer, had first proposed the idea in 1946, but there were too many technological challenges to overcome first.

As Nancy found out, there were human challenges as well. It would cost a great deal of money and require a lot of time and research to even design a space telescope. But the money came first. Nancy and NASA had to convince Congress that launching a telescope into space was worth every penny because of the promise of advancing our understanding of the universe.

She and her superiors held many dog-and-pony-show dinners for men with political power who lacked scientific backgrounds. For ten years, she wrote congressional testimony that was then given to Congress by her male counterparts. Funding the Hubble was a hard road, and NASA was rejected many times. Even after Congress approved, there were plenty of vocal naysayers.

Mother, Should I Trust the Government?

Nancy retired from NASA in 1979 and tried to leave the project in capable hands, but it suffered major financial, engineering, and management problems that went beyond any single person’s control. The proposed Hubble launch was set for 1983, then 1986, but was further delayed by the Challenger disaster. It was finally put into orbit on April 24, 1990.

Nancy credits her successes to a mixture of luck, determination, and her ability to speak and write well. She was never discouraged by the educators who insisted that she had no place in astronomy or physics. She simply knew it was what she wanted to do, and she believed in herself.

What mattered most to Nancy was advancing space exploration. She has had a very active retirement, traveling all over to teach and lecture. She is an outspoken advocate for women in the sciences, and takes every opportunity to encourage girls who are interested in astronomy.

[ad_2]

Source link